At the Global Junior Challenge 2017

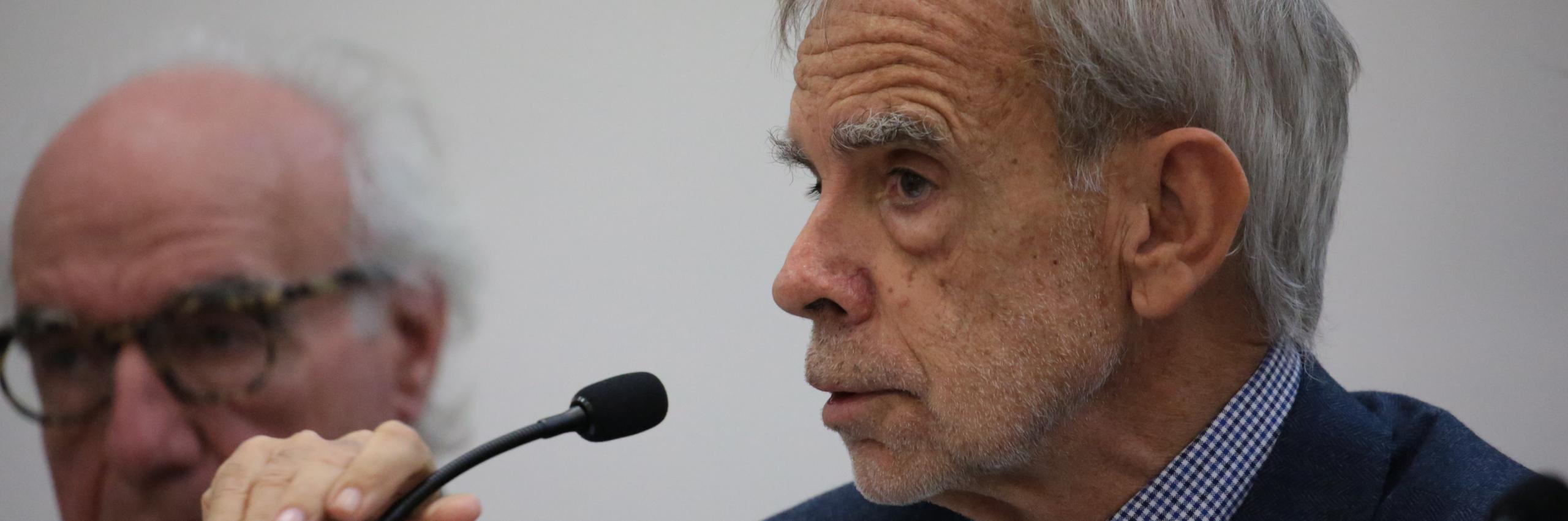

We would like to honour the extraordinary figure of Luca Serianni (Rome, 30 October 1947 – Roma, 21 July 2022) through two contributions. The first is very short. It’s from the last lesson he presented before retiring in 2017: “Dear Students, I know I’m speaking as a rector, but to me you represent the State, and I trust that this declaration will leave a mark on your future.” The second, entitled Vocabulary and Common Language Didactics, was shared by the linguist at the Global Junior Challenge 2017, in memory of his friend and colleague Tullio De Mauro (Torre Annunziata, 1932 - Rome, 2017).

Vocabulary and Common Language Didactics

The active interest of Tullio De Mauro for school is one of my fields of work. It’s an interest with certain fundamental characteristics. The first is that De Mauro was one of the few who managed to turn scientific interest towards the issues of schools. [...] And there are two more fundamental aspects. The first is civil commitment, a characteristic of Tullio, who from the outset embarked on a scientific activity to explore the conditions of schools and their related problems, true illiteracy and schooling issues. The second element was that Tullio De Mauro was one of the few who truly understood and grasped the opportunities provided by technological transformation. If we make this our starting point – an environment called “Digital World” – this is true proof that, unlike his peers, he managed to apply new methods to new opportunities with great coherence, intellectual aperture and personal grace. Let me make a few reflections, especially in terms of didactics and vocabulary. Why? Because vocabulary was an issue that De Mauro often addressed and in which he made significant contributions, if we think about his lexicological work, the Grande Dizionario della Lingua Italiana, and his characterization of words in terms of frequency, degree of use, fundamental definition and all that which is not fundamental. In particular, the attention to school and vocabulary also derives from De Mauro’s interest in the 1970s for the Don Milani’s approach, which can also be found in the Tesi del Giscel[1], written and published in 1975 and that clearly reveal De Mauro’s influence, although he is not the official author. There are two points in particular that I would like to remember here. Point 6 addresses the inefficiency of traditional linguistic pedagogy, which “concentrates solely on spelling” – without any success considering that “spelling mistakes can even be made by erudite individuals.” My comment is not an invitation to write badly or ignore the use of apostrophes. It’s an invitation to weight the various factors at play in linguistic education, which also includes spelling, but this does not solve the problem; the problem is mastery of vocabulary. And point 8, which fundamentally, according to De Mauro and the Giscel Theory is “the compass is the communicational function of a spoken and written text and its parts, based on it’s the real interlocutors to which it is addressed.” This is decidedly beyond a fundamental vocabulary, that constituted by words, grammatical forms such as “the” and “being”, or words such as “cat” or “vinegar.” It is far more – and it’s a basic vocabulary – that allows us a significant contact with a written language. It’s a moment, one of many, in which linguistic competence is knowledge, the possibility that every student must have and fully exploit of coming into contact with the written world, the intellectual world. I’ll give you just one example. I would like, as an educator, for any schooled thirteen-year-old to have no doubts that words like hepatitis or hepatic are connected to “liver.” And I’m not speaking about a scientific or classics lyceum. Any student. Just like “hydric” is related to water, “pyromaniac” to fire; and with more than a basic idea of what bribery and embezzlement are. Certainly, they are juridical terms, but they are also part of our everyday cultural horizon. They are in the news and addressed by newspapers and tv news shows. And, in addition to this normal vocabulary, I would also like that they learn to move confidently in the area that is technically referred to as “collocation.” In other words, the connections and the semantic solidarity amongst words. I may use the word “allocate” for a sum reserved for public works, or for another type of license, or for a company service, such as the provision of electric energy. So, I could neither allocate “advice” or “alms.” These two sentences are wrong. Allocating advice for semantic reasons, allocating alms because it is an individual, single act, which has no public determination that the verb implies. I’ll stop here as five minutes are up, or almost. I just wanted to avoid a banalisation of De Mauro’s positions. It’s true that he always insisted on the notion of fundamental vocabulary, but this in no case means stopping at the vocabulary that an Italian child (or that of immigrants who have been schooled in Italy) possesses naturally. Schools must expand this talent e allow children and then adolescents to view the more complex, varied and differentiated, world of written culture.

[1] Intervention and Study Group in the Field of Linguistic Education